|

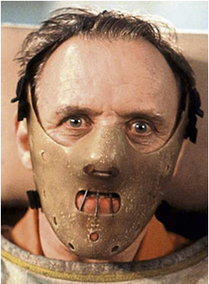

I'm delighted to welcome novelist Daryl Rothman to my blog! Daryl has written this guest post, The Ties That Bind: Five Traits Shared by Great Suspense Novels. Over to you, Daryl! You just can't put it down...  Have you ever experienced that with a book? Most people have, if they’re lucky. Of course, I’ve lost myself so thoroughly in a great novel that I’ve run late for important engagements, snuck in reading time at work, and read entire days away. And it’s glorious. But have you ever stopped and considered what kinds of books most commonly ensnare you in this manner? Any great book can do so, but for many people, suspenseful, psychological thrillers comprise the most usual suspects. The brilliant, beautiful psychotherapist whom we learn will kill her husband; the murder of a 12-year-old girl which evokes haunting memories for an Irish detective; the fiendish plans and eventual execution of murder and attempts at moral justification in mid-19th-century Russia; a brilliant but profoundly troubled computer hacker who finds herself in the crosshairs of espionage and murder in high-society Sweden; a fledgling FBI agent tasked with culling secrets from an imprisoned murderer before another serial killer strikes again. What are the common traits that keep us on the edge of our seats (or upright in our beds, biting our nails as we compulsively, helplessly turn page after scintillating page)? Why can’t we put these books down? I am a bit leery of authoritative, definitive lists—the greatest beauty of great books, after all, is that they belong to the reader, gifted by talented scribes, suffused with memorable characters and compelling details, plots and stories, but belonging to each reader nonetheless, to see, feel and absorb as only she can. So any list detailing traits of great books is inevitably incomplete. But after considering my own favorites and other perspectives, I have compiled here a list of 5 traits I believe many great suspense novels share, and offered examples for each. 1. Front-row seats  Great suspense novels confer upon readers the ultimate of vantage points. Often, though not always, this manifests via dramatic irony, wherein the reader is privy to something important that a main character(s) is not. In "The Silent Wife", we come to know—and are directly advised that the protagonist does not know—that she will commit murder. Top authors are not coy with their readers (despite the plot twists we’ll discuss a bit further down)—they display complete trust in us, bestowing ringside seats to the show. In Dostoevsky’s classic "Crime and Punishment", we again learn early of nefarious plans and so the suspense resides not in discovering Raskolnikov’s murderous contemplations, but in whether and when he shall indeed execute them, and what the ramifications will be. Foreshadowing, when properly presented, lurks in this dark realm as well, gilding our gaudy seats with golden touches of spine-tingling hints and anticipation. 2. Clockwork universe  In most good books, and most assuredly in great suspense novels, the clock is ticking. Sometimes literally: 24 hours until the bomb explodes… one week before the mob returns for their money… 60 minutes (naturally) before the sands pass through the hourglass in the witch’s castle. Even if it is not stated so explicitly, there is almost always a race against time in one way or another—some decision or action which must be made or taken within SOME limited time frame in order to achieve or avoid a pretty significant result. Many of the best thrillers have a trigger action, that act or decision which, whether intentional or otherwise, sets the gears of the story’s plot in motion. Whilst not a novel, the recently concluded and highly-acclaimed drama "Breaking Bad" offered a perfect example of a trigger mechanism: when Walter White makes the decision to cook and sell meth, he triggers a series of dramatic, violent, often bizarre but in the end seemingly inevitable events. This article does a great job elaborating, and is a worthy primer on many of the principles of the clockwork universe in fiction. But back to the suspense novels, and the matter of ticking time: "The Silence of the Lambs" and "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo" both mine the murky depths of serial killers, and the reader gets and feels the urgency. The protagonists must find the killer before he claims his next victim. A literary clockwork universe also is tinged with notions of destiny and fate—tension is heightened as the reader is imbued with the realization that the protagonists are not only on a collision course with the antagonists, but that the odds seem somehow preordained against them. 3. Unbelievably (yet made believable) high stakes  We must not only care about the protagonists, but also about what they care about. A protagonist may be richly developed, beautifully-textured and wholly relatable… yet if all she cares about is whether the prolonged winter has adversely affected her spring garden, this is probably insufficient to compel the reader to keep turning pages. Ah, but if the prolonged winter has adversely affected her spring garden, in which she was growing a hybrid plant whose seeds contained the cure to a worldwide pandemic, suddenly the stakes have soared higher. In “Lambs” and “Dragon Tattoo” the stakes are pretty darn clear—stopping a serial killer is about as intense as it gets—but even taut tales of murder are often suffused with additional, more nuanced stakes. "In the Woods" is the story of an Irish detective also on the trail of a killer, but the pursuit stirs embers of a long-repressed trauma directly connected to the crimes he’s investigating. Throw in an intense and ultimately ill-fated romance with his partner, and the stakes for Detective Ryan are not only high, but layered and complex: can he cope with the awakening memories which begin to plague him anew?... can he and Det. Maddox navigate the murky waters of their smoldering relationship while remaining focused enough to solve the deepening mystery? But it’s more than just really high stakes—the higher they are, the more intense or even fantastical—the greater the burden on the author to make them seem plausible. This is accomplished not merely by creating stakes which resonate with a reader’s notions of possibility—for so often we read to escape the constraints of reality and limited possibility—but by creating a world wherein it seems possible—even inevitable—for the characters. 4. Twists and yet more twists  A great thriller has twists—usually lots of them. But if we are to distinguish between ordinary and extraordinary works of suspense, it again comes down to execution (sometimes literally). J But the great ones don’t steep their manuscript full of twists merely for the sake of it, or for (almost always) fleeting shock value alone. The best twists knock us on our backsides but we gladly bolt back up, smiling: thank you sir, may I have another? They knock our socks off and we revel in the surprise yet perhaps even gently chide ourselves for not seeing it coming but also loving that we didn’t. Fowles’ "The Magus" is replete with dizzying, imaginative twists, yet when taken in composite they thread together in the tapestry of the psychological playground (god games) the author has presented. I’ve had the privilege of guest posting for speculative fiction author and owner of the highly-acclaimed "Helping Writers Become Authors" website K M Weiland, who wrote a fantastic post on how to write killer plot twists. Note her exhortation early on: poorly executed twists are not only ineffective but can be counterproductive and even insulting. The great ones get it right. 5. When all's said and done, CHARACTER  This is so obvious as to become all-too-often-neglected. There is a tendency when pondering literary genres to become so fixated upon the various traits and devices that define each. To wit, this post. Here we are dissecting common threads which weave through great suspense novels. And this is good and well for a discussion of what we love to read and why, but a danger lurks for the scribe who loses herself in these considerations. An obsession with assuring one has included all requisite components and devices can result in a work that is gimmicky and trite. Look at me, I’m a suspense novel—did you see all those great twists? Eh? Eh? Meh. The great thrillers unveil these components seamlessly, seemingly effortlessly (I say seemingly because great writing is hard work) and takes us for the ride of a lifetime. But even for those which have nailed every other great element, if they fail to deliver memorable characters, the work will ultimately ring hollow, fall flat. Strong characterization is incumbent upon any great story, even more so, I’d argue, in great thrillers, for even though conventional wisdom may suggest successful orchestration of all other suspense elements perhaps minimizes the requirement of epic characters, the opposite is in fact true: terrific plotting, harrowing danger, cliffhanger twists all harbor the potential to outshine the characters themselves. But the best suspense novelists understand their work will be all the more riveting, resonate more enduringly, if all the components complement, rather than compete with one another, and strong characters are an essential ingredient. What do you think of first when I mention "Silence of the Lambs"? A haunting psychological expose on the twisted minds of serial killers and the inner-workings of the FBI? Maybe. But more likely you think of him, the wonderfully puerile Dr. Hannibal Lecter. Or her, the sublimely vulnerable but fiercely courageous Agent Starling. Characters. They are the living vessel through which all the other elements find voice. Lists and resources When these and the myriad additional traits of great suspense novels come together, it is something to behold. Symphonic. Scintillating. Evoking and provoking. More than anything, one hell of a read. Here are some great lists of terrific suspense novels: https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/psychological-suspense https://www.amazon.com/Best-Sellers-Books-Psychological-Thrillers/zgbs/books/10491 https://www.ranker.com/list/best-suspense-novels/ranker-books What do you think? What are some of your favorite suspense novels and what were the traits that grabbed you the most? Please share your thoughts in the comments! Thank you, Daryl! I'd like to thank Daryl Rothman for this terrific blog post. Daryl is a father, author, early childhood leader and public speaker. He received his BA from the University of Illinois, MSW from Washington University and is a licensed clinical social worker. His website features his blog, short stories, publications, guest interviews, and news about his novels. He has guest-blogged for K M Weiland, CS Lakin, Joanna Penn, Firepole Marketing and published flash fiction for The Hoot and flash fiction for Kal Ba Publishing. Daryl may be found on Twitter, Linked In and Google+. From early in life he harbored three aspirations: become a father, become a writer, and become a ballplayer for his hometown Cardinals. He is blessed to have achieved the first, is happily continuing his journey regarding the second and he will neither confirm nor deny holding out hope for the third.

0 Comments

For my fourth novel, 'The Second Captive', I adopted a two-part structure, together with a prologue and epilogue. Not particularly unusual, but it got me thinking. Just how weird and wacky can a novelist get with the way he/she constructs a novel? And are there any examples I could share with my blog readers? It turns out there are plenty. Here are five examples of novels that take a different approach to the classic chapter-by-chapter structure. 1. 'Dolores Claiborne' - Stephen King 'Dolores Claiborne' is a 1992 thriller by Stephen King, narrated by Dolores herself. The novel is unusual in that there are no chapters or other section breaks. Instead, the book is a single continuous piece of prose that reads like a monologue. It sounds strange, but it works. Here's a summary of the plot. Dolores Claiborne is being interrogated by the police, under suspicion of murdering her wealthy employer, an elderly woman named Vera Donovan whom she has looked after for years. The two women had a difficult yet close relationship. Dolores is adamant that she is innocent; however, she does confess to killing her husband, Joe St. George, almost thirty years before, after finding out that he sexually molested their fourteen-year-old daughter. Dolores's confession develops into the story of her life, her troubled marriage, and her relationship with her employer. Along the way we also get glimpses into the personal lives of the police officers interrogating her, disclosed through Dolores's commentary, which demonstrates an astute grasp of human nature. 2. 'The French Lieutenant's Woman' - John Fowles 'The French Lieutenant's Woman', written by John Fowles in 1969, is a historical fiction novel. It's unusual in that the narrator intervenes throughout the novel and later becomes a character in it. Furthermore, he offers three different ways for the narrative to end. (No plot spoilers, I promise!) After the first ending, the narrator appears as a character sharing a railway compartment with the male protagonist. He tosses a coin to determine the order in which he will portray the other two possible endings, emphasising their equal plausibility. Here's a summary of the plot. Sarah Woodruff, the 'Woman' of the title, also known as 'Tragedy', lives in Lyme Regis as a disgraced woman, supposedly abandoned by a French ship's officer named Varguennes who has returned to France and married. She spends a lot of time on The Cobb, a stone jetty where she stares out at the sea, thus increasing her mysterious reputation. One day, Charles Smithson and Ernestina Freeman, his fiancée, see Sarah walking along the cliffside. Ernestina tells Charles something of Sarah's story, and he becomes curious about her. He has several more encounters with Sarah, and ends up falling in love with her. Returning from a journey to Ernestina's father, Charles has the choice of either returning to Ernestina or visiting Sarah. It's at this point that the first possible ending kicks in, triggering the appearance of the narrator in Charles's railway carriage and the other endings. Intriguing! 3. 'Slaughterhouse Five' - Kurt Vonnegut The novel boasting the unwieldy title of 'Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death' was written in 1969 by Kurt Vonnegut. It's a satirical novel that's partly autobiographical, being based on Vonnegut's World War Two experiences, particularly the fire-bombing of Dresden. Its structure is unusual in that the story is told in a non-linear order and events become clear through various flashbacks (or time travel experiences) involving the narrator. He describes the stories of Billy Pilgrim, who believes himself to have been in an alien zoo and to experience time travel. Here's a summary of the plot. Billy Pilgrim is a disoriented, fatalistic, and ill-trained American soldier who refuses to fight in the Second World War. He is captured by the Germans and transported to Dresden where he and his fellow prisoners are housed in a disused slaughterhouse in Dresden. Their building is known as "Schlachthof-fünf" ("Slaughterhouse Five"). During the fire-bombing, the prisoners of war and their German guards hide in a cellar, causing them to be among the few survivors. After the war ends, Billy suffers post-traumatic stress disorder and is put into psychiatric care. Once released, he marries a woman called Valencia Merble, and they have two children: a son, Robert, and a daughter named Barbara. Years later, on Barbara's wedding night, Billy is captured by an alien space ship and taken to a far-off planet, where he meets a porn star. She and Billy fall in love and have a child together. He is then sent back to Earth to relive past or future moments of his life. In 1968, Billy and a co-pilot are the only survivors of a plane crash. Whilst recovering, he shares a hospital room with a Harvard history professor. Billy talks about the bombing of Dresden, with the professor claiming it was justified. After Barbara takes him home, he sneaks out and drives to New York City. That evening he wanders around Times Square, visiting a bookstore featuring pornography, which brings back memories of his former love. Later, he guests on a radio show where he talks about his time-travels, culminating in being kicked out of the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep and time-travels back to 1945 Dresden, where the book ends. 4. 'Pale Fire' - Vladimir Nabokov This novel, written in 1962, is unusual in that it's presented as a 999-line poem entitled "Pale Fire" by the fictional John Shade, with a foreword and lengthy commentary by an academic colleague of the poet, Charles Kinbote. Together these elements form a narrative in which both authors are central characters. The reader can chose to read 'Pale Fire' in the normal linear fashion, or by jumping between Kinbote's notes and Shade's poem. The interaction between Kinbote and Shade takes place in the fictitious town of New Wye, Appalachia, where they live close to each other. Kinbote writes his commentary in a tourist cabin in the equally fictitious western town of Cedarn, Utana. Canto 1 of Shade's poem includes his early encounters with death and what he believes to be the supernatural. Canto 2 centres on his family and the apparent suicide of his daughter, Hazel. Number 3 focuses on Shade's search for knowledge about an afterlife, whilst 4 offers details regarding his daily life and his poetry, through which he attempts to understand the universe. Kinbote acquires the manuscript, overseeing the poem's publication, telling readers that it lacks only line 1,000. In his role as co-narrator, he tells three stories, one being his own, especially his friendship with Shade. Kinbote's second story deals with King Charles II, "The Beloved," the deposed king of Zembla, claiming he inspired Shade to write the poem by recounting King Charles's escape to him. The final story is that of Gradus, an assassin dispatched by the new rulers of Zembla to kill the exiled King Charles. In the last note Kinbote makes, to the missing line 1000, he tells how Gradus killed Shade by mistake. Isn't that all weird and wonderful? 5. 'The Unfortunates' - B S Johnson B.S. Johnson's 1969 experimental novel 'The Unfortunates' consists of 27 unbound chapters in a box. The first and last chapters are specified but the other 25 can be read in any order. These range in length from a single paragraph to twelve pages. The author explained this unusual structure by saying it was a better way of conveying the mind’s randomness than the imposed order of a bound book. Here's a summary of the plot. A sports writer is sent to Nottingham on an assignment, only to find himself confronted by ghosts from his past. As he attempts to report an association football match, memories of his friend, a tragic victim of cancer, haunt his mind. Let's hear from you!As I mentioned above, this post is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to unusually structured novels. What ones have you read that go beyond the norm in terms of structure? Perhaps you're a novelist yourself who's written a book that's a bit different. Leave me a comment and let me know!

As part of my 'Five' series, today's blog post examines some of the devious ways fictional murderers endeavour to conceal their crimes. Warning - by its nature, this post contains plot spoilers. If you're OK with that, then read on... 1. Apparent lack of motive  One way to escape detection as a murderer is to have no apparent motive. A great example is portrayed in Patricia Highsmith's 1950 thriller 'Strangers on a Train'. Architect Guy Haines is in love and wants to marry. There's just one catch - he already has a wife. What's more, she's unfaithful. On a train journey, Guy meet Charles Bruno, a psychopath keen to kill his father. They get chatting and Bruno proposes an ingenious solution to their issues - an exchange of murders. Bruno will kill Guy's errant wife if Guy returns the favour and murders Bruno's father. Bruno is convinced this will work because neither of them will have a motive for the murder they commit, meaning that the police will have no reason to suspect either of them. Guy's mistake is that he doesn't take Bruno seriously. However, Bruno kills Guy's wife while Guy is away in Mexico, and then informs Guy of his crime. Although shocked, Guy hesitates to turn Bruno in to the police. The longer he remains silent, though, the more he implicates himself. In the coming months, Bruno makes increasing demands to pressurise Guy into fulfilling his part of the bargain. After Bruno starts writing anonymous letters to Guy's friends and colleagues, the pressure becomes too great, and Guy murders Bruno's father. What an ingenious idea! Of course, Bruno's plan begins to unravel once a private detective establishes a connection between Bruno and Guy - but otherwise it might have worked... 2. An unshakeable alibi  Many novels exploit the idea of an unbreakable alibi, one firmly placing the culprit elsewhere when the murder was committed. An obvious way to do this is to make the time of death appear different from what it really was. Even skilled medical examiners can’t always pinpoint the time of death exactly, after all. Let's look at Agatha Christie’s 'Evil Under the Sun' (1982). Arlena Marshall, a famous and beautiful actress, is strangled while she, her husband Kenneth and her stepdaughter Linda are at the Jolly Roger seaside hotel. At first, it appears that no-one staying at the resort could have been responsible, but in fact the murderers have manipulated time so it provides a solid alibi for them. Until Hercule Poirot steps in to investigate... How did they do this? Easy. One of Arlena's murderers set Linda's watch 20 minutes forward. Then she asked Linda to check the time, thus giving the guilty pair an alibi for the supposed time of the murder. Later, the same person adjusted the watch back. Simple yet clever, don't you think? 3. Death by natural causes  If you're a fictional character about to commit murder, what better way to conceal your crime than making it appear a natural death? No murder investigation, a quick burial... it has its advantages. One of the best-known examples is Arthur Conan Doyle's 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (1902). When Sir Charles Baskerville is found dead on the wild moorland near his home, the cause of death is pronounced a heart attack. The elderly man suffered from a weak heart and blame is placed on a family curse after the footprints of a giant hound are reportedly near the body. According to legend, a spectral hound from hell patrols the moors, ready to bring death to the men of the Baskerville family following an ancestral pact with the Devil. Can Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson protect Sir Charles's heir from meeting a similar fate? Sir Charles's death is, of course, no accident, but murder made to look like a heart attack. Sir Charles was known to be frightened by the curse, elderly and with heart problems, something his killer used to his advantage. The murderer reckoned without Sherlock Holmes's legendary powers of deduction, though! The plot is contrived, sure, but the descriptions of the bleak moors are so incredibly atmospheric and the narrative so creepy that somehow the reader overlooks the unlikelihood of the novel's events. 4. Making murder appear an accident  Following on from the above, another popular fictional murder method involves faking an accident. I recently read Peter Høeg’s 'Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow' (1993), which demonstrates this kind of murder. In the novel, a young boy, Isaiah Christiansen, falls to his death from the roof of the Copenhagen apartment building where he lives. Isaiah had captivated the heart of the normally rude and surly Greenlander Smilla Jasperson; he seemed the only person capable of penetrating the hard exterior she presents to the world. Distressed by his death, Smilla is drawn to the scene of the accident. When she gets there, she finds clues in the snow that lead her to believe that the boy’s death was not accidental. Thanks to her Greenland upbringing, Smilla is an expert in all matters snow and ice-related, knowledge that she brings to bear as she begins to ask questions. Before long, Smilla discovers that some dangerous people are determined to hide the truth. Her search for answers leads her back to her homeland, where she uncovers the connection between Isaiah’s death and some long-hidden secrets. 5. Making murder look like suicide  A notable example of this murder method occurs in the 2013 novel by Robert Galbraith, 'The Cuckoo's Calling'. (Robert Galbraith is the pen name of J K Rowling, famous for the Harry Potter series of novels). In the book, Cormoran Strike, a private investigator with more than a few issues of his own, is hired by John Bristow, the adopted brother of famous supermodel Lula Landry, otherwise known as 'Cuckoo'. Lula's death is the result of falling five stories from the balcony of her Mayfair apartment building and has already been ruled a suicide. John Bristow, however, suspects otherwise. Strike is initially reluctant to take on the case, having read extensive media coverage of it. At first he's unwilling to reopen such a thoroughly investigated case. As he talks to those close to Lulu, including her security guard, personal driver, uncle, friends and designer, doubts emerge in his mind. Gradually Strike comes to realise that the circumstances of her death are more ambiguous than he imagined. Who wanted her dead, and did her personal fortune of ten million dollars provide a motive? What fictional murder methods appeal most to you? What kind of dastardly demises do you prefer in the novels you read? Do you like ones that are simple and perhaps more realistic, such as faking an accident or suicide, or do more complex killings float your boat? Perhaps something along the lines of the classic 'locked room' sub-genre of crime fiction, in which the murder seems impossible and has usually resulted from a contrived yet ingenious set of circumstances. Leave a comment and let me know!

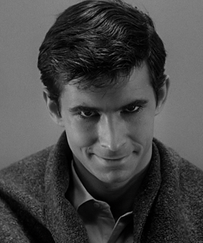

Anthony Perkins in 'Psycho' Anthony Perkins in 'Psycho' My readers already know I like to throw a psychopath or two into the mix when I write my novels. It's interesting that most of the respondents to a character competition that I ran said that, if chosen, they want to be cast as one of the bad guys! I think this taps into 'the shadows of the mind' theme of my own books, the dark side of our nature that many people harbour yet keep firmly in check. We're normally decent, law-abiding citizens, but we love to read about psychopaths, those dark, twisted individuals who transcend all boundaries to live life on their terms. Why else would crime, horror and thriller fiction be so popular? In this post, I've taken five of the most famous fictional psychopaths, and examined what makes them so memorable. 1. Patrick Bateman - American Psycho  American Psycho is a novel by Bret Easton Ellis, telling the story of Patrick Bateman, a wealthy Manhattan businessman and serial killer. The novel is narrated in the first person by Bateman, who charts his life for us, murders included. He frequents nightclubs with his colleagues, snorting cocaine and swapping fashion advice, whilst all the time engaged to marry socialite Evelyn Richards and dealing with his fractured family relationships. After killing Paul Owen, one of his colleagues, Bateman takes over his victim's apartment, using it as a venue to conduct more murders. All the while, his grip over his urges lessens as the level of his sadism increases. Bateman indulges in rape, torture and mutilation, with a spot of cannibalism and necrophilia thrown in for good measure. To make matters more bizarre, he talks about the murders to his colleagues, who refuse to take him seriously, and then he begins experiencing hallucinations. The book examines whether Bateman is the victim of some psychotic delusion about being a serial killer, or whether what he’s describing in this stream-of-consciousness novel has really happened. Well, it's pretty clear Patrick Bateman displays many classic psychopathic characteristics! Shallow and largely concerned with material gain and superficial matters, he treats everything as a commodity, people included. Placing such distance between himself and his behaviour enables Bateman to excuse his actions, even ones as gross as cannibalism. Hence his remark after dining on a woman's flesh: ‘I just remind myself that this thing, this girl, this meat, is nothing.’ Women are definitely objectified throughout the novel, being reduced to the level of the ultimate consumable – meat. Relationships mean nothing to Bateman. His friends all appear alike to him, to the extent that he often confuses one for another. His love life is equally meaningless. Engaged to the shallow Evelyn Richards, their relationship is characterised by mutual loathing, and it is made clear they only stay together for social reasons. So why does Patrick Bateman kill? In true psychopathic style, he murders many of his victims because they make him feel inadequate, usually by having better taste than he does. This is a man to whom fashion, style, and social approval mean everything. As a serial killer, he slaughters indiscriminately, with no preferred type of victim and no consistent method of killing. Men, women, animals, even a child – nothing and nobody is off-limits for this man. Definitely one of the most chilling psychopaths we’ll be examining today! I believe Patrick Bateman fascinates us so much because he taps into the unease many people feel about unchecked consumerism, typified by the obsession with celebrities, gossip and fashion. Is this where our love of such things will lead, to individuals so shallow and twisted that they murder indiscriminately, in a society that appears uncaring about their crimes? Food for thought... 2. Hannibal Lecter - The Silence of the Lambs  The Silence of the Lambs, written by Thomas Harris, is the sequel to his novel Red Dragon. Both novels feature the cannibalistic serial killer Dr Hannibal Lecter. Who, having read the book, will ever eat fava beans again without this man invading their thoughts?! Here's a summary of the plot. Jack Crawford, head of the FBI’s psychological profiling division, asks Clarice Starling, a young trainee, to present a questionnaire to the highly intelligent forensic psychiatrist and cannibalistic serial killer Hannibal Lecter. Lecter is serving nine consecutive life sentences for a series of brutal murders. Crawford's real intention, however, is to obtain Lecter's assistance in the hunt for a serial killer nicknamed ‘Buffalo Bill’, who skins his female victims after killing them. Lecter and Starling engage in a twisted game of traded information, in which he offers her cryptic clues about Buffalo Bill in return for details from her difficult childhood. Lecter's psychological make-up is explored in greater detail in Thomas’s other books, which reveal he was traumatised as a child by witnessing the murder and cannibalism of his younger sister. Thomas portrays Lecter as a cultured and sophisticated man, enjoying refined tastes in music and art, having served on the Baltimore Philharmonic Orchestra's board of directors. He is well educated, highly offended by bad manners in others, and speaks several languages. Not the type of character that immediately springs to mind when we think of serial killers, which helps to explain why he's so compelling. The man's an interesting juxtaposition of a violent serial killer along with a model of politeness and refinement, in stark contrast to the uncontrolled madness we often associate with sequential murderers. Although let's not forget the cannibalism - that's hardly refined behaviour! 3 - Annie Wilkes - Misery  Misery is one of Stephen King’s horror novels. The narrative focuses on Paul Sheldon, a writer who pens mass-market appeal romances featuring the heroine Misery Chastain. Sheldon is rescued from a car crash by former nurse Annie Wilkes, who takes him to her home and cares for him, assuring him she’s his number one fan. When she discovers, however, that he’s killed off Misery at the end of his latest book, she becomes enraged, forcing him to write a new novel modifying the story. Sheldon discovers an old scrapbook of Annie’s, and learns from the newspaper clippings inside that she is a serial killer, who has murdered her own father, her college roommate, and several patients at the hospitals where she worked. Wilkes ends up holding Sheldon captive, treating him brutally. In one memorable chapter, she chops off one of his feet with an axe when he attempts to escape, then cauterises the wound with a blowtorch. Sounds like the actions of a psychopath to me! Annie Wilkes masks her warped nature behind an initially engaging front. The novel portrays her as paranoid, and suggests she may also have bipolar disorder, hidden behind her cheery facade. In the novel, she clearly suffers from depression as well as issues with self-harm, over-eating and an obsession with romance novels. In the way she holds sway over Sheldon, she displays all the characteristics of the ultimate control freak, desperate to wield power over her latest victim. In meeting Annie Wilkes, Paul Sheldon encounters misery of the greatest depth, before finally reclaiming his life and his writing at the end of the novel. It's a good job not all authors require such an impetus to discover their muse! Why does Annie Wilkes hold such enduring appeal? It may be partly because we're unused to the notion of female serial killers, especially ones who outwardly appear as homely and ordinary as she does. The contrast between this dumpy, dowdy, middle-aged woman, a former nurse, and her horrific crimes, is enormous. 4. Tom Ripley - The Talented Mr Ripley  The Talented Mr. Ripley is one of Patricia Highsmith’s novels, written in 1955, and her first one to introduce the character of Tom Ripley, who appears in four other books by her. Ripley is a young confidence trickster living in New York, who is asked by a local shipping magnate to persuade his son, Dickie Greenleaf, to return from Italy to join the family business. Once in Italy, Tom becomes almost obsessed with Dickie and his wealthy lifestyle, which eventually grates on the man, as well as annoying his girlfriend Marge. Sensing that he is about to be cut loose by his new friends, Ripley murders Dickie and assumes his identity, living off his victim's trust fund. He manages to evade the suspicions of Dickie’s friends and father, as well as the Italian police, with everyone believing Dickie must have committed suicide. Tom's machinations end in a curious mix of triumph and paranoia, as he inherits Dickie’s fortune via a will he forged, but our charming psychopath is left with the uncertainty of never knowing if and when he’ll eventually get found out. In subsequent novels, Ripley involves himself in several more murders, often coming close to being caught or killed, but always escaping detection. Highsmith introduces some background material that may partly explain Ripley’s psychology. Orphaned at age five, he was raised by his aunt, a cold, stingy woman who mocked him, leading him to attempt to run away as a teenager. Highsmith's portrayal of Ripley is as a suave, agreeable and utterly amoral con artist, capable of great charm. In many ways, he resembles our friend Hannibal Lecter. Like Lecter, Ripley enjoys the finer things in life, spending time painting or studying languages. Also, like the good psychiatrist, he comes across as polite and cultured, disliking people who lack such qualities. He's also devoid of conscience, admitting in a later novel that guilt has never troubled him, although he claims to detest murder unless it is necessary. Ripley's character engages us, drawing the reader into the metafictional con that he perpetuates on us. This is a man who's cultured, charming and quick thinking, living the good life as he cheats and murders his way around Europe. A lifestyle that pulls us into the novel with its seductive appeal - no wonder both the book and its film version have proved so popular! 5. Cathy Trask - East of Eden  An amazingly powerful book that, for me, recovered quickly from its sluggish beginning to become enthralling. Based on pre- and post-lapsarian themes, the novel follows the relationship between Adam and Cathy Trask as Steinbeck's parallel to the Biblical Adam and Eve, along with the tension between their sons, Caleb and Aron. The novel seems to be primarily about love, as well as examining the effects of its absence. Cathy Trask, who we're concentrating on here, is unable to love anyone, even herself, and her coldness destroys her husband and her son Aron. Cathy, later known as Kate, bears many of the hallmarks of a psychopath. A twisted character, this, one capable of recommending that her husband toss their new-born twins into a well. Some critics have commented that her character lacks credibility, but I'd guess this reflects more the social attitudes towards women at the time of the book's publication. She's amoral and psychopathic, something that may well have offended 1950s sensibilities about women's roles. She is, after all, no domestic goddess or even a good wife or mother. With respect to the Biblical themes of good and evil, Steinbeck moves beyond representing Cathy as Eve, tempted by the serpent in the Garden of Eden; Cathy is the serpent as well as Eve. He emphasises this by portraying Cathy in snake-like terms; for example, when she swallows, her tongue flicks around her lips. In the book, Steinbeck describes Cathy as having a malformed soul, being cold and, in true psychopathic style, incapable of caring for anyone. Her misdeeds start with false accusations of rape and proceed to her setting fire to her family's home, killing both her parents. After being rescued by Adam when badly injured and subsequently marrying him, she gives birth to twin boys, before shooting her husband in the shoulder to escape the monotony of motherhood and married life. She ends up working as a prostitute in a local brothel, renaming herself Kate, eventually inheriting the business after murdering the owner. Steinbeck portrays Cathy as a delicate blonde whose beauty fools most of the people she encounters, her true nature being evident in her eyes, which he describes as cold and emotionless. Samuel Hamilton, a minor character in the novel, says that “the eyes of Cathy had no message, no communication… they were not human eyes”. Why does Cathy Trask entrance the reader so much? There's the fact that, like Annie Wilkes, she offers the novelty value of being a female psychopath. She's ordinary, too, although not to the same drab extent as Annie Wilkes. No, she's more the kind of psychopath we’re likely to meet in real life, rather than being an out-and-out con artist like Tom Ripley or a rarefied socialite like Patrick Bateman. Neither is she driven by the same dark forces that urge Hannibal Lecter to kill. Instead, she's a woman who goes about her daily life as we all do, but unlike the rest of us, she kills whoever stands in her way, having been born soulless, evil from birth. Who's your favourite fictional psychopath?  In this blog post, I've only been able to examine a tiny proportion of the vast array of fictional psychopaths that novelists have brought us throughout the years. Google 'famous fictional psychopaths' and you'll get over a million results! I chose these five characters because they cover both male and female, young and old, rich and poor, ones created through circumstance (Hannibal Lecter) and those born evil, such as Cathy Trask. What sociopathic characters have been memorable for you? Perhaps Jack Torrance from Stephen King's The Shining? Frederick Clegg from John Fowles's The Collector? Or is Amy Dunne from Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl more your style? Leave a comment and let me know! Warning - plot spoilers! Warning - by its nature, this blog post contains plot spoilers! It's impossible for me to reveal how these five novelists created their fictional murders without giving away essential elements of the plot. If you're OK with that, then read on... An incredible (and edible!) murder weapon  As part of my 'Five' series, in today's post I'll examine five unusual fictional murder methods. Crime writers often endeavour to come up with ever more creative ways to murder their characters, despite the fact that more orthodox methods such as guns and knives tend to be more convincing. Most people have heard of 'death by icicle' in both books and movies, and I'll share an example later. One of the most famous murder methods employed by fictional writers is the one used by Roald Dahl in his short story 'Lamb to the Slaughter'. The story tells of a wife who, after learning that her husband plans to leave her, decides to kill him. She bludgeons him with a frozen leg of lamb, then cooks the meat and serves it to the police officers who investigate her husband's death. Ingenious, huh? What a great way to dispose of a murder weapon! And yet another twist on the theme of death by ice. 'Lamb to the Slaughter' is a wonderful short story, but novels are more my thing. So let's examine five examples in which the authors have given their characters ingenious methods for carrying out their murderous intentions. We'll start with P.M. Carlson's 'Murder in the Dog Days'. 1 - 'Murder in the Dog Days' - P.M. Carlson  'Murder in the Dog Days' by P. M. Carlson (1990) is a great example of what's known as 'the locked room mystery'. In a story of this genre, a crime, usually murder, is committed in circumstances that appear inexplicable. As the name suggests, a locked room is involved, one in which the murderer apparently could neither have entered nor left. Here's a brief plot synopsis of Carlson's novel. On a sweltering summer day, (the temperature is highly significant) reporter Olivia Kerr and her husband Jerry invite Olivia's colleague Dale Colby to the beach. At the last minute, Dale decides to remain behind, and his dead body is discovered later on in his locked office. Already an ill man, Dale dies as a result of heatstroke when the temperature of his study reaches an intolerable level. His killer contrives the murder by manipulating the heat in the office via a thermostat, raising it during the day and then readjusting it before the body is discovered. As the office door is bolted on the inside, the crime scene appears to be a perfect locked room murder. 2 - 'Busman's Honeymoon' - Dorothy Sayers  'Busman's Honeymoon' (1937) is one of Dorothy Sayers's novels involving Lord Peter Wimsey. Wimsey is on honeymoon with his new wife, Harriet, at Talboys, an old farmhouse that Wimsey has bought for her. On the morning after their arrival, they discover the former owner, Noakes, dead in the cellar with head injuries. The house was locked and bolted when the newly-weds arrived, and medical evidence seems to rule out an accident, so it appears he was attacked in the house and died later, having somehow locked up after his attacker. Another locked room - or, for the pedantic, locked house - murder! By all acounts, Noakes was a thoroughly dislikeable man, and as the police investigation continues, a number of people emerge as suspects. The killer turns out to be Crutchley, a local garage mechanic who also worked as Noakes's gardener. He planned to marry Noakes's niece and get his hands on the money she would inherit in her uncle's will. The ingenious method Crutchley used involved setting a booby trap with a weighted plant pot on a chain, triggered by Noakes opening the radio cabinet after locking up for the night. 3 - 'The Religious Body' - Catherine Aird  An interesting concept - convents aren't normally places one associates with violent murder. In 'The Religious Body', published in 1966, Inspector C.D Sloan has the task of solving the death of Sister Anne, who has been murdered, stashed in a broom closet, and then thrown down a flight of stairs into the cellar. A most unholy happening! But how was Sister Anne killed? There is no apparent murder weapon to explain the blunt force trauma wounds inflicted before her tumble down the cellar steps. The answer is intriguing and, as the saying goes, hidden in plain sight. Catherine Aird's fictional murderer kills Sister Anne by delivering the fatal blows with one of the newel posts of a staircase. This unusual weapon is rendered more deadly by the heavy wooden ball atop its shaft. After the murder, the post is returned to its original position, to remain right under Inspector Sloan's nose as he investigates the death. 4 - 'A Big Boy Did It and Ran Away' - Christopher Brookmyre  Christopher Brookmyre introduces not one but two ingenious murder methods in his novel 'A Big Boy Did It and Ran Away' (2001). As a student, the novel's character Simon Darcourt swaps dreams with his friend Ray Ash about the two of them becoming future rock stars. Fifteen years later, older and soured by life, they're struggling with the disappointments that have come their way. Whilst Ray seeks refuge from his parental responsibilities in online games, Simon chooses a much darker coping mechanism. For him, relief comes through serial killing, mass slaughter and professional assassination. Simon's first murder in the novel is with a mercury-laden icicle, which melts away before the body is discovered. This fictional murder device, sometimes transmuted into an ice bullet, has been used many times, starting with Anna Katharine Green's novel 'Initials Only' (1911), in which a young woman is killed by an icicle shot from a pistol. Simon's second murder is that of a drug dealer. Darcourt mixes a lethal amount of heroin into a takeaway curry and knocks on the man's door, claiming the food is a pre-paid order from that address. Too greedy to resist, the dealer dies, makes it appear as though his death was from the drugs he supplied. A great example of an unhealthy appetite! 5 - 'Matricide at St Martha's' - Ruth Dudley Edwards Perhaps the most contrived murder we'll examine today occurs in Ruth Dudley Edwards's 1995 novel 'Matricide at St Martha's'. St. Martha’s College, Cambridge, has been operating on a shoestring for decades, before being left a huge sum of money in a former student's will. The result? Large-scale infighting amongst the various college factions. Before long, one of these, the Virgins, led by Dame Maud Theodosia Buckbarrow, is taking the lead, its members believing the money should be spent on scholarships. Then Dame Maud is murdered... So how is this dastardly deed accomplished? Well, our victim climbs a ladder in the college library, the ladder being one of those that slide across the front of the bookcases via grooves in the wall. Normally, there are brakes at the end to stop the motion; however, in this case, the murderer has removed them. Following Dame Maud's own vigorous push to the ladder, she hurtles to her death as it gathers speed, eventually catapulting its hapless occupant from the library window. Give me some more examples! I hope you have enjoyed this blog post! I'd be delighted to hear from you. Can you add any more examples to this catalogue of dastardly deaths? Have you read any novels where the murder method has struck you as unusually clever? Or maybe one that has made you throw the book aside and shout 'No way, Jose! That would never happen!' Leave a comment and let me know!

'I don't waste time with novels...'  'I don't read novels,' someone once told me, his tone dismissive. 'I don't waste time with bullshit. Know what I mean?' My response? I chose not to reply, but to deflect the conversation. Had I answered his question, I'd have done so with an emphatic negative. Apart from the comment being provocative, making it to a lifelong bookworm like me was pointless. No, I don't know what he meant about novels being bullshit. Never have, never will. I suspect anyone reading this blog is likely to side with Team Maggie on this one! It's not that I don't understand why people don't read fiction. I do, despite my lifelong love of books. You see, I'm someone who doesn't care much for music. This often attracts gasps of horror from music aficionados, who refuse to believe me. 'You must enjoy music!' they tell me. 'Music is life!' For them, perhaps, but not for me. Each to their own, as the saying goes. Music doesn't feature in my existence and that's my choice. The difference between my fiction-loathing friend and me is that I'm not dismissive about what I don't enjoy. To dub all music bullshit would be ridiculous; it's a huge source of pleasure for many. I suspect that's what grated about my friend's comment. Fair enough if he doesn't enjoy fiction. But to brand all novels as bullshit strikes me as plain daft. Of course, some people pride themselves on a philistinic approach towards cultural matters, and that's their right. For me, however, fiction, especially in the form of novels, has enriched my life beyond measure. Let's examine five ways in which great novels enhance our lives. 1. They're a great means of entertainment and relaxation

2. Reading keeps our brains sharp, increases our cognitive skills and boost our vocabulary A study published in 2013 showed that fiction enhances connectivity within the brain, especially in the area of language. Makes sense, doesn't it? As we read, we're studying sentence construction and spelling without being conscious we're doing so. 3. Books can educate us An example is 'Sophie's World' by Jostein Gaarder. Clothed in the story of fourteen-year-old Sophie Amundsen lies a wonderful history of philosophical thinking, which teaches as it entertains. As mentioned above, I've also read Gaardner's novel 'The Castle in the Pyrenees', another educational read. This book focuses on a debate between a Christian and an atheist, examining issues such as the origin of the universe and life after death. All wrapped up in an intriguing story about the consequences of a hit-and-run accident in Norway. Education without the classroom! 4. Novels provide both social and political commentary

5. Novels, especially the classics, add beauty to life Lovers of Thomas Hardy's books thrill to his lyrical descriptions of the Dorset countryside. Fans of Charles Dickens marvel at his skill in creating characters, such as Wackford Squeers and the Artful Dodger. In adding beauty to our lives, books also contribute to our cultural heritage. Imagine a world without literature. For me, if not my fiction-hating friend, Earth would be a planet lacking the wonder that novels provide. Events such as the destruction of books under China's Qin Dynasty or the Nazi book burnings are akin to sacrilege for me. Works of cultural significance trampled under the boots of repressive regimes - it's no coincidence that the need to control and a hatred of the arts often walk hand in hand. Literature, when allowed to flourish, makes an invaluable contribution to our lives. As does music, for those who love it! Let's hear from you! What novels have you found educational? Do you agree that books enrich our lives and add beauty to them? Are there any roles books fulfil that I've not covered? Leave a comment and let me know! |

Categories

All

Subscribe to my blog!

Via Goodreads

|

Join my Special Readers' group and receive a free copy of 'Blackwater Lake'!

|

Privacy policy Website terms and conditions of use

Copyright Maggie James 2018 - current date. All rights reserved.

Copyright Maggie James 2018 - current date. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed